The Complexity Of OSHA’s PSM Standard

FDRsafety continues to encounter situations where worker training is incomplete or lacking, especially in safety. Unfortunately, we find that much of this training has no foundation… Let me explain.

I recently attended the 2nd Annual Process Safety Summit in Washington DC on Oct 15-16, 2019. The Summit brought together safety and legal professionals from chemical manufacturing, petroleum refining, paper and other industries covered by OSHA’s PSM Standard and EPA’s RMP Rule, with officials from the relevant regulatory agencies. It was a great opportunity to interact and network with this group.

Recent OSHRC rulings have increased the complexity of determining the boundaries and scope what is covered by the PSM standard. The OSHRC Wynnewood refinery compounded industry’s challenge in determining what is and is not covered by 29 CFR.1910.119. For those of you who deal with PSM, you know this is a critical first step in determining if a traditional risk-based approach will suffice from a compliance perspective. Unfortunately, there are no clear-cut answers.

To help our clients that deal with PSM, we would draw your attention to the top 5 most cited standards from PSM NEP :

- Mechanical Integrity

- Process safety information

- PHA

- Operating procedures

- Management of change

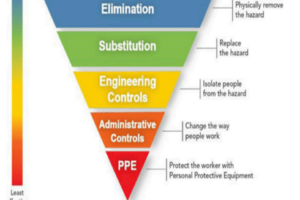

Items 1 and 2 are both heavily focused on RAGAGEP, Recognized and Generally Accepted Good Engineering Practices. FDRsafety’s experience and expertise can provide valuable guidance on the complex and sometimes confusing issue of RAGAGEP. Using accepted ANSI standards, we are able to make use risk assessment, feasible risk reduction using the hazard control hierarchy and acceptable risk to solve real-world problems. When deciding that risk mitigation is needed, the concept of feasibility comes into play to demonstrate due diligence in complying with the OSH Act.

Whether our risk assessment Train-The-Trainer sessions or consultation on specific issues, our team of Senior Advisors can help.

First, we fully understand that appropriate industry practice is to have an experienced worker training a new employee. That practice has been in existence for decades and is sound, with a major caveat. If you do not have a written procedure (safe operation, machine specific lockout, shutdown, etc.) or other form of standard work, there’s a high probability that you have variation in what is being taught.

I have done hundreds of Task Based Risk Assessments and handled expert cases for OSHA or personal injury where there is no foundation for the worker “training.” In most cases, there is nothing but transfer of knowledge via on-the-job learning. In a few cases, the documentation of procedures is so voluminous as to be of little value for the new worker doing the job alone.

“Show me” is a simple and fast way to assess the foundation for worker training. I look for point of use instruction. When you have a lockout procedure located in a supervisors desk or some location other than point of use, it’s likely that the worker is not taking the few minutes to walk over and begin thumbing through a procedure when he or she is trying to get the machine back into production.

In some cases, good point of use instruction is augmented by warnings, signs or operational standard work (showing what machine controls to push and their sequence for a given task) These training aids are simple, visual and contain information that comes from the experienced workers. I do not like standard safety signs and warnings because they typically mean little to the worker. On the other hand, asking the experienced worker for his/her input on what they would use to better train their own child or friend often elicits excellent thoughts that increase awareness and enhance learning.

Not only does this approach reduce risk but it can help reduce the amount of training time for the new worker. US industry is undergoing a massive loss of experienced workers as “Baby Boomers” leave the workforce. It is my experience that the lead time for a new worker learning to run an automatic machine or operation can vary from 2 – 5 months. That’s a long time to get the worker up to speed for production, safety and efficiency.

Use “show me” and improve training aids at Point of Use. One approach for achieving “acceptable risk” is an adjunct question for the experienced worker, “Would you be comfortable with your child doing this task with the training and point of use instruction that is in place?”

FDRsafety provides hands-on “Train The Trainer” learning for those who are interested in putting this approach to use in their company.

Mike Taubitz spent many years in top positions at General Motors, including stints as Global Safety Director and Global Regulatory Liaison. He has a strong interest in lean manufacturing and its relationship to safety and in sustainability, and is recognized internationally for his expertise in machine guarding. He assists clients in creating efficient and effective safety programs, especially in manufacturing environments.

For more advice, please reach out to FDRsafety.