OSHA’s Use of General Duty Clause in a Way Never Intended

Throughout its 46-year history, OSHA has had the authority to utilize Section 5(a)(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, commonly known as the General Duty Clause, to address “recognized hazards which are causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees,” and where there are measures that are “feasible, available and likely to correct the hazard.” Section 5(a)(1) was included in the OSH Act to give OSHA a means to address “recognized hazards” where no OSHA standard existed, but it was never intended as a replacement for rulemaking. Indeed, as expressed by Congressman Steiger in the Legislative History of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, S. 2193, P.L. 91-596, pgs 1216 and 1217, there were considerable fears of the potential for abuse of the Section 5(a)(1) General Duty Clause. Congressman Steiger (one of the Co-Sponsors of the OSHAct) in fact stated:

The conference bill takes the approach of this House to the general duty requirement that an employer maintain a safe and healthful working environment. The conference reported bill recognizes the need for such a provision where there exists no existing standard applicable to a given situation. However, the requirement is made realistic by its application only to situations where there are ‘recognized hazards’ which are likely to cause or are causing serious injury or death. Such hazards are the type that can readily be detected on the basis of the basic human senses. Hazards which require technical or testing devices to detect them are not intended to be within the scope of the general duty requirement. It is also clear that the general duty requirement should not be used to set ad hoc standards.

Notwithstanding this admonition, OSHA has repeatedly used the General Duty Clause to address an ever widening range of subjects including such alleged hazards as ergonomics, workplace violence, crowd control, killer whales, Broadway theatre acts and combustible dust.

With respect to the issue of combustible dust, following a 2008 sugar dust explosion at Imperial Sugar Corp. in Port Wentworth, Georgia, which resulted in fourteen fatalities and numerous injuries, OSHA issued a revised National Emphasis Program (NEP) on Combustible Dust which focused on, “industries with more frequent and higher consequence dust incidents.” Status Report on Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program, OSHA Directorate of Enforcement Programs, October 2009. Included in the NEP was a list of alleged “combustible dusts,” such as metal, sugar, plastic and wood dusts, each with what OSHA contended were long industry histories of explosions and deflagrations, which required that employers take extraordinary measures to protect their employees from combustible dust hazards. Also included on the list of alleged combustible dusts, however, was a substance called carbon black, a carbonaceous material used in the manufacture of tires and other rubber products, which gave tires their dark color and elasticity. Unlike other dusts listed in the NEP, there had been no record of carbon black ever exploding or even burning in the more than 100-year history of the tire making industry.

OSHA also provided in the NEP that the explosive nature of the combustible dust could be determined by subjecting these dusts to scientifically established tests such as Minimum Explosive Concentration (MEC), Minimum Ignition Temperature (MIT), Minimum Ignition Energy (MIE), and Kst value. According to OSHA, the combination of these tests could be used to establish a true and precise profile of the explosibility of the dust and the likelihood that it could cause a catastrophic event. However, when subjected to these tests, carbon black was shown to be extremely unlikely to ignite and had an extremely low capability of exploding or causing a deflagration. In fact, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) noted that carbon black could not even be ignited by burning magnesium and did not present an explosion hazard.

Notwithstanding this record, in 2010, OSHA commenced inspections against Cooper Tire & Rubber Company at its tire making plants in Findlay, OH, Tupelo, MS and Texarkana, TX. OSHA thereafter issued alleged Willful violations against the Findlay and Tupelo plants contending that the company had engaged in alleged Willful violations of the General Duty Clause, the Hazardous Locations Standard, 29 C.F.R. 1910.307(c)(2) and the Housekeeping Standard, 29 C.F.R. 1910.22(a), among others, by failing to utilize explosion protection and other engineering and administrative controls to protect its employees from explosion/deflagration hazards resulting from Cooper Tire’s use of carbon black in its tire manufacturing process. Following the Findlay inspection, Cooper Tire was placed in OSHA’s Severe Violator Enforcement program (SVEP) which led to the inspections at Tupelo and Texarkana and the resulting Willful violations against the Tupelo plant in 2012. The citations were vigorously contested by Cooper, followed by years of litigation and eventually a trial. Cooper’s efforts in litigating the citations were followed with great interest by all the tire and rubber manufacturing industries because those industries had consistently maintained that carbon black was not a fire or explosion hazard as claimed by OSHA. At issue, among others, were, not only the alleged Willful violations and associated penalties, but the extraordinary abatement costs which Cooper Tire could incur attempting to abate the alleged explosion/deflagration hazards at its tire making facilities in Ohio, Mississippi and Texas,

As later noted by the Court in its 2015 Decision and Order, “After more than three years of litigation, including extensive discovery spanning more than two years, with hundreds of interrogatories and document requests, and twenty-one depositions, the case proceeded to a bench trial on December 2, 2013, which lasted two weeks with seventeen witnesses testifying over the course of the trial.” On March 17, 2015, Administrative Law Judge John Gatto of the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission issued his Decision in the matter of Perez v. Cooper Tire & Rubber Company OSHRC No. 11-1588 In a more than 60-page Decision and Order, Judge Gatto vacated all of the alleged combustible dust citations in the case, based on his conclusion that the Secretary had fundamentally failed to prove that carbon black, or mixtures of carbon black, as used in Cooper Tire’s manufacturing process, was a combustible dust “hazard” within the meaning of 5(a)(1) or the cited standards.

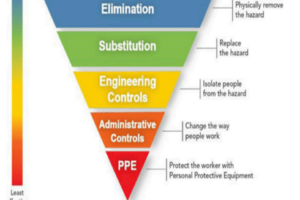

First, the Court held that the Secretary failed to prove the elements required to prove an explosion/deflagration hazard in part because the Secretary failed to follow its own Combustible Dust NEP in testing the dust sample at issue by scientifically established tests, such as Minimum Explosive Concentration (“MEC”), Minimum Ignition Energy (“MIE”), and volatile content, and instead relied on narrowly focused Kst tests which were designed to evaluate the theoretical capability of a material to explode (common dirt also has a Kst value) but failing to determine the probability or likelihood that such a dust would ignite and explode in the actual workplace setting. It is important to note that the inherent properties of carbon black make it extremely difficult to ignite, and the Secretary did not have any data to establish that any of the identified ignition sources found in Cooper Tire’s tire making plant could actually ignite the dust sample. Moreover, the entire tire making industry and the U.S. rubber manufacturers had never recognized carbon black to be a combustible dust hazard and, moreover, the NFPA had published the results of scientific studies showing that carbon black was one of the least likely carbonaceous dusts to ignite or explode and that even burning magnesium, at almost 3000 degrees, could not ignite carbon black. Fire Protection Handbook, Vol. I, Sec. 7, Ch. 4, “Storage and Handling of Chemicals,” 20th Ed., National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) (2008) Indeed, while offering evidence that Cooper Tire had experienced several fires over its more than 100-year history, OSHA could not identify a single fire that had ignited carbon black nor any carbon black explosions or deflagrations of any kind. Moreover, by failing to perform the above tests, the Court reasoned, “the Secretary failed to evaluate, much less establish, the properties of carbon black dust as it existed in the Tupelo Plant, and, instead, presumed that the cited conditions created an explosion hazard.” Therefore the Judge vacated all of the alleged violations set forth in the citations.

Second, the Court rejected the Secretary’s reliance on the NFPA requirement that combustible dust could not be allowed to accumulate in quantities greater than 1/32 of an inch in depth- a de facto value which OSHA had utilized for years in citing employers for alleged Serious Housekeeping violations stemming from alleged explosion/deflagration hazards created by accumulations of combustible dusts in workplaces. The Court first reasoned that the sections of the NFPA on which the Secretary relied were actually property protection standards which, in this case, did not even apply to Cooper Tire because its facilities had been constructed prior to the NFPA’s enactment. The Court reasoned that, if the basic purpose of the NFPA standard (including, for example, the 1/32 “requirement for dust accumulations), as used by OSHA in this case, was to address and correct a specific and already identified hazard, and not simply a purely administrative effort designed to detect or discover possible violations of the OSHAct, then the Secretary was using the NFPA provisions as an ad hoc standard. Accordingly, the Court held that OSHA must utilize the administrative rulemaking process.

Without question, the OSH Act does provide in the General Duty Clause a means for OSHA to protect employees from “recognized hazards” which create serious and life threatening safety risks to employees. However, the General Duty Clause was never designed to operate as an ad hoc rule to remedy every perceived workplace “hazard” which OSHA seeks to “discover” and eliminate. This is particularly true in the absence of a history of “high consequences incidents” evidencing the existence of a truly “recognized” and “readily apparent” hazard which has already caused or is likely to cause serious injuries or death to employees. As the Cooper Tire case demonstrates, OSHA must be circumspect in pursuing cases of this kind and judicious in the manner in which it commits its limited resources to pursuing theoretical “hazards,”which have never caused a single injury. At the very least, if OSHA intends to use NEPs or similar publications as a means of attempting to create implied “recognition” of a hazard, OSHA should follow its own publications in determining whether a true “hazard” exists.

The case is captioned, Perez v. Cooper Tire & Rubber Company, OSHRC Docket No. 11-1588(March 17, 2015). Attorneys for Cooper Tire & Rubber Company were Jonathan Snare, Jason Mills and Dennis Morikawa, with assistance by Emily Bieber and Brandon Brigham.